‘Strange Phenomena’: Tracing Surreal Feline Metamorphosis between Kate Bush, Fini &Deren.

- The Debutante

- Apr 27, 2020

- 15 min read

Updated: May 5, 2020

This is a transcript of a conference paper presented on 12th December 2019 at ECA's 'This Woman's Work: A Kate Bush Symposium' by Molly Gilroy.

Penelope Rosemont deplores in Surrealist Women: An International Anthology (1998) that “surrealism has been pronounced dead so many times that few writers have bothered to look at the plentiful evidence of its present day vitality.” Framed by this call for contemporary female surrealists to be acknowledged, I aim to excavate the surrealist visual grammar within Kate Bush’s oeuvre. Though never self-defining as a surrealist, Bush holds avant-garde poetics and surrealist sensibilities of the juxtaposition of realities and sur-realities, esoteric and evolving transformations. I shall begin to fill this contemporary research gap, exploring the cross-generational visual alliances to between Kate Bush and female surrealists, specifically, to the Ukranian-born avant-garde filmmaker and theorist, Maya Deren and the Argentinian painter and fashion revolutionary, Leonor Fini. This paper is a working progress, seeking to align this triage of artists through examining their polymorphic identities and gestural states, of a female identity in metamorphic flux, and their interest Woman as an ‘I’ that is artist, producer, designer and muse.

Leonor Fini, Kate Bush, Maya Deren

Despite Surrealism ‘ending’ after the death of its founder Andre Breton in 1966, this paper moves towards locating a vitality of contemporary female surrealists, particularly in the case of interdisaplinary artist, Kate Bush. Originated by a close circle of male friends, with Breton and Louis Aragon at its realm, Surrealism, at its roots, was arguably exclusionary to women’s creative energies; femininity repeatedly reduced to a passive, dismembered mannequin. Though in Breton’s 1924 Manifesto of Surrealism he exclaims that “the mere word ‘freedom’ is the only one that still excites me”, woman’s freedom from her role as the ‘passive mannequin’ and ‘femme enfant’ was questionable. Breton’s notion of ‘freedom’ had a gendered limit; liberation for male member’s creativity to blossom, while justifying and perpetuating female degradation.

Part of Kate Bush’s own surrealist artistic ‘anarchy’ lies in disrupting the phallocentric spheres of production, defying the construction of her body as a mere ‘pin up’, object and muse...

The Female Surrealists’ art of the period, partially in reaction against Surrealism’s phallocentric origin and exclusion, have provided distinct legacies, those which often outshine those of their male counterparts. Roginal Cardinal argues that there has arisen a lively succession of women artists who evoke dream places; ‘angels of anarchy’. Bush becomes fertile ground in which future revisionary commentaries of the female surrealists can thrive. Part of Kate Bush’s own surrealist artistic ‘anarchy’ lies in disrupting the phallocentric spheres of production, defying the construction of her body as a mere ‘pin up’, object and muse, reflecting that “I was aware that [production] was male-dominated. What mattered was being able to experiment on my own terms.” Bush continues elsewhere, that “people weren’t even away that I wrote my own songs. The media just promoted me as a female body. It's like I’ve had to prove that I’m an artist”. It is this defiant assertion, of herself as not as a ‘woman artist’ but as creator, her own muse, that aligns Bush with her female surrealist predecessors. Bush constructs and de-constructs herself as an intermedial corporeal body, caught and thriving between liminalities of human/animal/female; an assertive subject; “That's what all art's about - a sense of moving away from boundaries that you can't in real life. Like a dancer is always trying to fly, really - to do something that's just not possible.”

This state of flux, outside the phallocentric music production industry, mirrors the the ‘Daughters of Surrealism’s, such a Leonor Fini and Maya Deren, outright refusal of the label of surrealism, and ‘membership’ within the group. Deren always rejected definitions of her work as ‘surrealist’; [quote] “I distinguish myself strongly from the surrealists although my films have occasionally a superficial resemblance to various surrealist films..."Fini also refused to join the ‘official’ movement of Surrealism; her marginality her own centrality to her own work of assertion; “I have never been very interested in ideologies, and I refused the label surrealist… I was never a surrealist. I preferred to walk alone.” With this framing in mind, I shall begin by exploring the visual alignment between Kate Bush, Maya Deren and Leonor Fini’s metamorphosis with the feline, in terms of ‘embodiment as negotiation’. This embodiment, as identified by Marsha Meskimnon, is an exchange and interaction between corporeal entities, that creates identities. In this case, the female body becomes a site of negotiation with the feline, to reach a state of metamorphic flux. Georgnia M.Covile has noted that animals frequently reflect the women of surrealism’s identity quest and imaginary escape into a different world, where they need not be dominated.

Leonor Fini 'The Coronation of the Pleased Cat' 1974

Leonora Carrington, Tarot Cards

Specifically for the surrealists it was the cat’s mythical ancestor of the sphinx that provided marvellous fascination. As Alyce Mahon writes “the myth of the sphinx was especially attractive, providing the perfect metatext for an exploration of forbidden desire, as well as encompassing the fantasy of the femme fatale…and a means of self-questioning.” The ‘companionship’ between the feline and the feminine can also be traced to the Rider Waite Tarot Card ‘Strength’. The surrealists were fascinated with the lyrical potency of Tarot cards, with both Dali and Leonora Carrington designing their own deck of cards. In the card, as the goddess/queen begins to tame the lion, physical contact uniting them in a moment of cathartic transference, the two bodes over-lay one another, moving towards a sphinx like metamorphosis. The tarot imagery strikes a visual rhyme with Fini’s ‘The Connotation of the Pleased Cat’, where there is slippage between the image and title of the painting, as it is the female who is coronated, blurring the boundaries between female and feline.

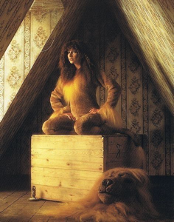

Bush’s second album, Lionheart (1978), depicts Bush dawning half of a lion costume, poised crawling on top of a transportation/carrier box. In an act of performative dressing up, Bush harnesses the ability to oscillate between and ‘put on’ states in monstrous ambiguity, both feline and female. Bush has noted the importance of fabric to humanity; “clothes are such a strong part of who a human being is”; human skin stitching itself into external fabric. Costume becomes a house for another internal skin, and in the album cover of Lionheart, a desexualisation of the female body. There is both a sense of the mundane familiarity in this image, Bush innocently merely wearing a fabric costume, and simultaneously, a vulgarity; her body cocooned within the animal. Such alliance and an uncanny fascination with the de-headed Lion, fragmented and vulnerable, also appears in this arresting portrait photo of 1978. The camera here is position in uncomfortable ambiguity; both ‘heads’ seem detached from the rest of their bodies, alive or mystically enchanted?

Kate Bush Lionheart 1978

In relation to Fini’s oeuvre, Rachel Grew notes the facilitating power of costume; to change the appearance, texture, shape and borders of the body of the wearer, to enact an uncanny monstrosity. This polymorphous flux, is key to the state of the ‘Bushian Feminine Multiform Subject’ as Deborah Withers has theorised. Through costume, the space in with the corporeal body and individual takes up, is extended, evolves and transforms. The fascinated repulsion is heightened by the slippage of the human form within the animal; the animal mealy a cocoon and almost embalming process for the female. As Withers notes, “the Bushian Feminine subject creates more room for people to exist within their own subjectivities, ‘room for life."

Almost in a cross-generational dialogue with Bush’s interest in performative metamorphosis, Fini states that, “To dress up…is an act of creativity. And in applying this to ones-self, one becomes other characters or one’s proper character. …It is one – or many – representations of the self…it is a creative expression of the raw state”. It becomes significant that Bush’s costume is not of the lioness, but of the lion. She upends the tight binaries of human and animal as well as male and female, moving towards a ‘raw state’ of androgynous hybridity. In this violent act of ‘de-heading’ and de-masquerade, Bush draws direct attention to a monstrous hybridity of the creature, just as Fini’s creations such as her 1954 ‘Sphinx’, which, as Grew succinctly notes, “revolt against the rational”. Fini’s protagonists can be murderous, and carnivorous; her felines as violent matriarchs. Like the de-headed female mannequins of surrealism that haunt the surrealism, Bush re-formulates and reclaims the de-headed, fragmented and violated mannequins that haunt surrealism of the female body, with independent ferocity, whilst taking on a revisionary version of the femme fatale.

Kate Bush Lionheart. Leonor Fini 'Sphinx' 1954

Here, visual grammar between these two ‘performances’ is stark. In both the cover for Lionheart, and Fini’s Petit Sphinx Gardien, there is a glimmer of light, in which both the hybrid creatures look towards ; their ‘raw states’ poised reaching towards enlightenment, escape and another sur-reality, poised and elevated above ground. Indeed, we are left to question the permanency of Bush’s state, not conjoined in the flesh like Fini’s sphinxes; is it a birth from within the animal or is she receding into the animal? It is this changeable ambiguity, this ‘in-betweenness’, that invokes both fascination and horror within the viewer, with such feelings similarly registered in Fini’s work, where the bodies of the corporeal female body become the non-human. Grew in relation to Fini, notes that:

“Such concurrent repulsion and attraction allies the monstrous with the uncanny: the familiar made strange and unfamiliar….a costume that makes a familiar human body become strange can be the focal point of a viewer’s simultaneous attraction and repulsion and therefore acts as the catalyst for the creation of an ambiguous monstrous body…It is allied to a feminine, liminal state of being, which can be shared by spectators of the monstrous body…Fini’s monsters retain their human form but change its constituent materials – from skin to scales and fur. In other words, Fini metamorphoses the borders of her bodies so that they become non-human”

The repulsive and intoxicating flux of being is what Bush linger upon; “All human beings are uneasy on some level, continual questioning going on which I think is good”. Fini viewed the act of costuming and dressing up as a creative act which reveals a manifold self; “When one dresses up one is able to experience being both one’s conscious self and someone else (or another, perhaps unconscious self) simultaneously”

Kate Bush Lionheart. Leonor Fini 'Petit Sphinx Gardien' 1943-44.

Bush’s sensual feline movements occur elsewhere in her oeuvre, yet in subtler and more sensual ways, as she roams and writhes within the trees in the Wuthering Heights music video, reminiscent of Maya Deren’s understated feline characteristics, in At Land of 1944. Deren quickly established herself as a key player in the New York art scene. The apartment she shared with Hammid became a venue for informal screenings of Meshes Of The Afternoon (1943), avidly attended by artists and writers. In the opening scene of At Land Deren crawls out of marine swept branches, her eyes darting across the screen, in a curious cat-like manor. As her body leaves the top of the frame, we see her head appear over the edge of a dinner table. This ‘boundary-less’ style of her film-making, places the female subject within and across the temporal gaps of each film frame. In this unique film-language, temporal and spatial surreality is achieved, of cinematic magic, where mundane logic is replaced by one of occult logic. Deren, as her own muse, is thus placed within a new temporality; her body fluid and unrestrained by a mundane logic and corporeal-boundaries. Here, the slow delicate movements elongate her limbs, in almost slow motion, as she peers out from beneath the table, her eye’s surveying, proceeding to slink across the table. While she does not wear the skin of the cat through costume, it is in her bodily movement that she reveals herself as more than human.

Deren demonstrates that the individual can be divided; in this case, her raw state has an uncanny layer of feline sensuality. Deren enacts her fascination with vertical time, and it is as if, Deren’s multiple self is reborn within the very texture of the film’s own ‘magic’ temporality, and imbued with the spirit of the feline. Indeed, Deren aligned the female witch with a feline companion, writing “this ‘independence’ of the accepted natural pattern upon which the normal are dependent, jives, of course, with the universal attributes of witches as being ‘solitary’, owning cats, since cats share their independence”. Alongside Deren’s interest vertical time, her curiosity with the occult and magic also developed during 1942-46, coinciding with the period in which the surrealist circle around Breton intensified its avant-garde engagement with myth and enchantment. Combining Deren’s theory of vertical expansion with her interest in esoteric magical transformation, the brief but visually arresting feline movements in At Land become part of a wider ritual transformation of the otherworldly, the feline, embedded within her own corporeal body.

To return to Wither’s notion that “the Bushian Feminine subject creates more room for people to exist within their own subjectivities, ‘room for life’” we can begin to trace a similar expanse for life in Deren’s vertical expansion cinema, projected onto an embodied feline-female. Deren’s cinema is one of a continual emergent whole, undercutting the assumption of a fixed perspective in a sensual proto-feminist aesthetic. Deren had summarised At Land as the female individual “struggling to preserve in the midst of such relentless metamorphosis of a constancy of personal identity”. We momentarily see through the eyes of the feline; a moment of inter-subjectivity and depersonalisation, a method in which Kate Bush moves towards in her album art for Lionheart, and her feline-sensual movements in Wuthering Heights (1978).

Bush sets herself up as both artistic creator and her own muse; an active role on both sides of the camera.

Metamorphosis and the magical occult is everywhere in Bush’s realm, with surrealist traces lying within Bush’s choreography, particularly within The Line the Cross and The Curve (1993), with such poetic visual resemblance of costumes to Leonor Fini’s ballet designs and the choreography of movement in Deren’s film Ritual in Transfigured Time of 1946. The 40 minuet film, directed by Bush, is part visual album, narrative film and choreographed ballet, with Bush drawing on her evolving journey with dance, taught by mime performance artist, Lindsey Kemp, who also stars in the film. Bush sets herself up as both artistic creator and her own muse; an active role on both sides of the camera. The hybridity of contemporary dance and ballet becomes a medium for cathartic release for female subjectivities and a surrealist device; the body becoming the medium that moves both between the conscious and the unconscious world.

The film opens in a topsy-turvey underworld; the camera spins in a 360 motion, unravelling a filmic realism, and we are twisted into the down-below of doubling and a dissolution of mundane reality. The film begins with the track ‘Rubber band Girl’; sonic and visual contemporary working together, embodying the flexibility, elasticity, endurance and transfiguration of the female body. Bush re-forms the surrealist notion of the constrained, idealised and passive 'femme-enfant’ (the woman-child); her own ‘Girlhood’ moving in unrestrained agency of contemporary dance; a refusal to remain static in a conclusive space.

In the following scene, Bush, playing herself, gazes into the dance mirror and lights a candle; acts which becomes the catalyst for the doubling and fracturing of the Bushain-Feminine Subject and the access of the esoteric alchemical Woman. In the highly stylised mise-en-scene which accompanies ‘And So Is Love’, the film moves towards a moment of eco-feminism, as Bush ceremoniously lays the bird to rest; with an ‘enchanted’ kiss The dance studio transforms into Bush’s arcane-laboratory, in the spirit of her female surrealist pre-cursors of Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington, cooking and artistically creating in their kitchen in Mexico in the 1940s. Whitney Chadwick has argued that “myth, magic and the occult joined together in shaping the surrealist image of woman as the repository of hermetic knowledge.” As the bird is laid to rest with Bush’s kiss, the ballet dancer, played by Mirander Richardson, breaks through the mirrored surface, in the spirit of Alice Through the Looking Glass, in which the surrealists were fascinated with. Through Bush’s play with the cosmic and occult, she inadvertently conjures the ballet dancer, as a twisted doppleganger drawn from the mirror surface. Indeed, I am reminded of Irigaray's notion in The Sex of ‘feminine mirrors’ of concavity, producing the ‘cultural reserve yet to come’; ‘the possibility of a space of representation for female sexuality’. The mirror, as a classic surrealist symbol, produces a ‘gestalt’ refraction, defying a fixed perspective of womanhood, of a body-double becoming in a transient process of metamorphosis.

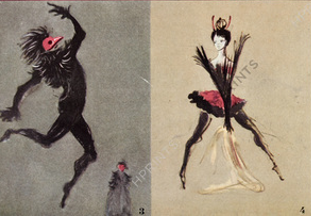

Above left to right: Leonor Fini 'Ruby Tutu' "Palais Garnier". July 28, 1947.

Leonor Fini 'Harlequin' Ballets de Paris 1949.

Below: Mirander Richardson in The Line The Cross and The Curve

There are captivating visual traces of costume design to Fini’s 1947 costumes designs for ‘The Crystal Ballet’ and the ‘Ball of Kings and Queens’. Bush’s villainous ballet dancer’s costume is sensually animalistic and ‘earthy’; her headpiece is made up of thorns and brambles, forming vegetal like horns, upending the boundaries between woman, nature and animal, sticking a powerful visual rhyme with Fini’s 1949 design . All at once, she is formidable and vulnerable; her hands bandaged, adding a layer of uncanny repulsion to the imagery of femininity.

Fini’s ‘Harlequin’ design is reminiscent of the playful Joker Tarot Card, where the headpiece once again is closer to devil-like horns; matriarchal violence always underpinning her feminine form, a visually pre-cursor to Bush’s costumes. Elsewhere, in the ‘Ruby Tutu’ Costume for, The Crystal Palace ballet, Fini repeats her fascination with the headpiece, with this design more conventionality feminine, and perhaps more akin to the ballet dancer in The Line The Cross and The Curve (TLTCATC). Given Fini’s friendship with Leonora Carrington, who was interested in Celtic myth, she may also have been aware of pagan horned deities. These deities, while also predominantly masculine, refer to the life and fertility of the earthly realm, effectively combining male/female, above/below, life/death in one figure. This Celtic association is traced in TLTCATC, with both Bush and Richardson’s costumes equipped with red ad black feather-like horns. Interestingly, in ‘The Red Shoes’ there is a Celtic lilt to the music. In this screen ‘duet’ Bush and the ballet dancer exchange creative energies; Bush offering her artistic ‘path’ and ‘heart’, in return for the red shoes. Yet, the sound-track is only Bush singing, and thus the visuals offer a disjunction; leaning us towards a reading of Bush and the ballet dancer as part of an interchangeable, and polymorphous self.

Kate Bush in The Line The Cross and The Curve, Leonor Fini's 'The Triumph of Chastity' (1954)

The uncontrollable power of the shoes propels Bush into the underworld, transforming her costume into a more sexualised one of black and red feather and horns, mirroring Richardson’s costume, with the notion of an exchange between corporeal identities again at play. Again, there is visual grammar with Fini’s ballet costumes and her 1954 design ‘The Triumph of Chastity’. Costume, for Bush and Fini, become catalysts for accessing and indulging in a manifold self. Indeed, Fini often interchanged costumes, moving from one character to another, creating a fluid identity between performative persona’s, of a body with multiple parts and identities. Cocooned with the androgynous, vegetal costumes Fini metamorphosis the extensions and borders of the bodies, so that they become non-human; a feature in which Bush’s own costumes moves towards through the use of black feathers, as if the characters have taken on parts of the fallen blackbird viewed at the film's beginning...

Moving away from Fini, Deren privileges the movement of the corporeal body, and the influence of choreographed performance on the aesthetic structure of her film, similarly reflected in Bush’s own film. While Bush’s ‘Rubber-band Girl’ is metaphorical, Deren, in Transfigured Time (1946), literally plays with an elastic, woven band, twisting it in an endless cycle; woman and cinema’s vertical elasticity at play once again. Deren’s film focuses on a uncanny female relationship, twisting new female sur-realities and cinematic architectures, in artistic collaboration and tension, just like the relationship between Bush and her own doppelgänger. Dance and magic become inseparable, and in both films, it is the presence of the female characters which drives the magical transformation and resolution; with male figures absent in the film’s resolutions. Indeed, Nobel notes “each film concludes with the lone female protagonist achieving some form of resolution with nature or the elemental world” much like Bush’s narrative conclusion, with the balance of ‘self’ resorted in the flames of the underworld.

Maya Deren in Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946)

The performance artists move in fluidity, almost non-choreographed expressionism. Deren’s ritual, of bodily transformation, becomes a “critical metamorphosis and above all, for some inversion towards life”. These gestural encounters of woman are part of Deren’s transgressive creation of the occult as a source of empowerment and prog-feminist emancipation. Deren certainly compared her process to that of a choreographer, stating for example that Ritual “is a dance” and talking about “the choreography of the whole”. Bush follows Deren’s meandering and often dream-like plot structures, with an entangled relationship between dance, physical performance, and the physicality and metamorphic flux of film. Paul Valéry, writing in 1936, provides a useful definition of dance in relation to more familiar bodily movement; “an action that derives from ordinary, useful action, but breaks away from it, and finally opposes it”. Such gestural operations are at play in both Ritual and TLTCATC, with both creative collaboration and tension between manifold female selves, as a dancerly exchanges between the figures and its spectators.

“A woman has strength to wait because she has had to wait. Time is built into her body in the sense of becomingness. She sees everything in the stage of becoming.”

Female surrealists have continued to thrive, through their work’s presence in contemporary female artists visual grammar, reinforcing the importance for matrilineage to be traced, in order to establish the links between female artists. Deren and Fini become symbolic avatars for Bush to extend their contemporary art-historical relevance, where as, Clare Johnson postulates “femininity can be understood as a relationship to time”, where it is through the ‘repetition’ of femininity, of inter-generational dialogues, temporal circularity, that new encounters and iconographies of femininities are achieved. Kate Bush is not the only musician who draws upon female surrealists; Laura Marling cites Leonora Carrington as a key inspiration for her, especially when understanding the role of the female ‘muse’ within artistry. I would like to suggest viewing the triage of ‘the line’ ‘the cross’ and ‘the curve’ as an emblem of Bush, Deren and Fini, lending us to understand female matrilineage as an integrated structure, yet with each individual occupying her own agency and independent. I hope I have begun to map Bush’s oeuvre and construction of ‘Woman’ as a body in flux, defying taxemic categories, destabilising the female body, whilst building upon the connective tissue, creative associations and visual grammar with Fini and Deren.

Maya Deren wisely reflected that; “A woman has strength to wait because she has had to wait. Time is built into her body in the sense of becomingness. She sees everything in the stage of becoming.” As this conference has highlighted, Kate Bush is still becoming, and though I have not been able to explore the triage of artists visual fascination with open doors, mirrors and keys, to enter otherworldly and sur-realities and dimensions of feminine becoming, I hope there will be time in my research to further explore such becomingness of Bush’s ‘strange phenomena’.

Thank you.

References:

Breton, Andre. Manifestos of Surrealism. The University of Michigan Press. 1962.

Bush, Kate ‘Egos and Icons’ Interview, 1993.

Cardinal, Roger, Angels of Anarchy: The Imagining of Magic. Manchester City Art Gallery, 2009.

Deren, Maya. ‘Anagram’. Maya Deren and the American Avant-garde. edited by Nichols, Bill. Berkeley: U of California, 2001. Print.

---.Smith Lecture, 1961.

Grew, Rachel. 'Feathers, Flowers, and Flux: Artifice in the Costumes of Leonor Fini'. Web.

Irigaray, Luce. Ethics of a Sexual Difference. Cornell University Press, 1993. Print.

Noble, Judith. "Clear Dreaming: Maya Deren, Surrealism and Magic." Surrealism, Occultism and Politics: In Search of the Marvellous. Taylor and Francis, 2017. Web.

Rosemont, Penelope. Surrealist Women: An International Anthology. University of Texas Press, 1998.

Withers, Deborah M. Adventures in Kate Bush and Theory. Hammer on Press, 2010.

Comments